Rooted in Tradition, Adapted for Today: Natural Dyeing from Hawaiʻi to the Bay Area

Connecting diaspora communities to ancestral practices through locally available plants

Yellow and red onion skins being prepared for a dye vat. Kekoa Creative.

Author's Note

This article serves as a gentle introduction to natural dyeing practices, honoring both traditional Hawaiian methods and contemporary adaptations for diaspora communities. It's important to understand that across ka pae ʻāina o Hawaiʻi, there have always been many traditional methods that varied between different islands, regions, and ʻohana. Each family and community developed their own techniques, passed down through generations of practice and experimentation.

The colors and results you achieve will vary based on countless factors: the specific region where plants are grown, local growing conditions, particular plant varieties, seasonal timing, water quality, and the many different dye production methods available to you. Traditional mordants, non-traditional mordants, fermentation techniques, and extraction methods all influence your final results - and that's part of the beauty of this practice.

My best suggestion is to experiment, have fun, and embrace the variations that come with working alongside nature. Remember that proper protocol is essential when entering any foraging areas, especially if you're not growing the plants yourself or sourcing them directly from others. For Kānaka ʻōiwi, I encourage offering pule through mele and oli such as "Noho Ana Ke Akua" or "Kūnihi Ka Mauna" before harvesting, as our kūpuna taught us to approach the ʻāina with respect and gratitude. Keep in mind that my cultural recommendations or historical anecdotes are not complete deep dives into the full aspect of these plants and materials. I am just sharing what I know from my own ʻohana as well as teachings from various kūpuna over my lifetime. From the traditional hawaiian perspective, it is understood that there are always more than one truths to everything, so be mindful and respectful in your reading.

This article is simply a starting point - a foundation for you to build upon as you make your own discoveries, develop your own techniques, and create your own relationship with the plants and colors that speak to you. Every dye bath is an opportunity to learn, and every result is a gift from the ʻāina.

E mālama i ka ʻāina, a mālama ka ʻāina iā ʻoe.

The Cultural Practice of Natural Dyeing in Hawaiian Tradition

In traditional Hawaiian culture, natural dyeing was a vital cultural practice that connected our kūpuna to the ʻāina and embodied the principle of mālama ʻāina. Each plant used for dyeing carried its own mana, its own story, and its own cultural significance.

Our ancestors understood that color was not just aesthetic; it was a form of communication, a way to honor the natural world, and a method of preserving cultural knowledge. The deep yellows from ʻōlena, the rich browns from kukui, and the vibrant reds from native plants weren't just beautiful—they were expressions of our relationship with the land.

Traditional Hawaiian Natural Dye Plants

ʻŌlena (Turmeric) - Curcuma longa

Perhaps the most well-known of Hawaiian natural dyes, ʻōlena produces brilliant golden-yellow hues that have been treasured for centuries.

ʻōlena. turmeric plant.

ʻōlena. turmeric rhizomes.

Plant Parts Used: Fresh or dried rhizomes (underground stems)

Colors Achieved: Bright golden yellow to deep orange-yellow

Extraction Method: Grate fresh rhizomes or powder dried ones, simmer in water for 30-60 minutes. The longer you simmer, the deeper the color.

Cultural Significance: It was often used to dye kapa (bark cloth) worn by aliʻi and during important ceremonies. ʻŌlena has significance in lāʻau lapaʻau, traditonal hawaiian medicine, as a key ingredient in both physical and spiritual purification, directly relating to mana and its quality. For kānaka, careful consideration should be taken when using this dye plant for objects potentially linked to ceremony and the potential for kaona.

Kukui (Candlenut) - Aleurites moluccanus

The kukui tree provides multiple dye sources, each offering different color ranges.

lau kukui. kukui tree leaves.

Plant Parts Used:

Bark: Produces rich reddish-browns and deep browns

Nuts: Inner shells yield lighter brown tones; burned nut elements and the collection of its char created deep black pigments

Leaves: Create yellow-green colors

Extraction Methods:

Bark: Strip outer bark, simmer inner bark pieces for 1-2 hours

Nuts: Crack shells, simmer inner shell pieces for 45 minutes; burn shell elements under an object and collect char material off of object by scraping

Leaves: Fresh leaves simmered for 30 minutes

Cultural Significance: A kinolau of Lono, Kukui represents light in darkness and was important to Laka, goddess of hula, as a symbol of guidance in ka ʻimi naʻauao. This significant tree in Hawaiian culture provided dyes for both ceremonial and everyday garments. There is much kaona in any use of kukui, and so care should be taken in both the intended and potential kaona surrounding the objects where any portion of this plant is used for dye.

Koa - Acacia koa

The magnificent koa tree yields beautiful earth tones from its bark.

koa tree with branches and seed pods.

Plant Parts Used: Inner bark (never harvest from living trees)

Colors Achieved: Reddish-brown, tan, and deep brown tones

Extraction Method: Simmer bark pieces for 2-3 hours for deep, rich colors

Cultural Significance: Koa is the word for bravery in ʻōlelo. Dyes from koa bark were often reserved for garments worn by warriors and chiefs. Specific spiritual kaona was implied with the associated warm reddish colors produced. Kapu was placed on various ulu koa, koa groves, by aliʻi since the wood was prized for making both waʻa (canoes) and mea kaua (war implements).

Noni - Morinda citrifolia

Different parts of the noni plant produce varying colors.

noni tree and fruit.

Plant Parts Used:

Roots: Produce vibrant yellows. Mixed with pigments made from ground corals produce various other colors such as reds and pinks.

Bark: Yields yellow and orange tones

Leaves: Create yellow-green colors

Extraction Methods:

Roots: Dig carefully, clean, and simmer for 1-2 hours

Bark: Strip and simmer for 45 minutes

Leaves: Fresh leaves simmered for 30 minutes

Cultural Significance: Noni was considered a plant of healing and spiritual cleansing, and its dyes were often used for ceremonial purposes. Traditionally, noni has always had very deep roots in lāʻau lapaʻau, and so should always be approached from a medicinal standpoint, with kaona in itʻs use as a dye plant associated with physical and spiritual healing.

Hau - Hibiscus tiliaceus

The hau tree provides subtle but beautiful colors.

hau. branches, foliage, and yellow flowers. kauaʻi. Kekoa Creative.

Plant Parts Used: Inner bark

Colors Achieved: Soft yellows and pale oranges

Extraction Method: Strip inner bark, simmer for 1 hour

Cultural Significance: Hau was valued for its versatility - the bark was used for cordage, and the dye colors were prized for everyday garments. Kapu was typically placed on the foraging of living hau plants by aliʻi due to it being such an important plant integral in many hawaiian art forms such as the making of kaula, iako for waʻa, and as lāʻau lapaʻau.

Diaspora Adaptation: Natural Dyes in the SF Bay Area

Living in the diaspora doesn't mean disconnecting from our cultural practices—it means adapting them thoughtfully to our new environment while maintaining their cultural essence. For us, the SF Bay Area offers an abundance of plants that can be used for natural dyeing, allowing us to continue this ancestral practice while honoring our new home.

Important Note: Always connect with local Indigenous communities to learn about native plants in your area. The Ohlone peoples are the original inhabitants of the SF Bay Area, and their knowledge of local plants is invaluable. Approach with respect, offer reciprocity, and remember that sharing knowledge is a two-way exchange.

Onion Skins - Allium cepa

One of the most accessible and reliable natural dyes available anywhere.

yellow and red onions.

Plant Parts Used: Outer papery skins (yellow and red onions give different colors)

Colors Achieved:

Yellow onion skins: Golden yellow, orange, rust

Red onion skins: potentially Deep reds, burgundy, purple tones (may sometimes achieve same tones as yellow onion skins)

Extraction Method: Collect skins for 2-3 weeks, simmer in water for 45 minutes. No need to mordant first - onion skins are naturally high in tannins.

Cultural Connection: While not traditional to Hawaiʻi, onion skin dyeing allows us to achieve similar golden tones to ʻōlena.

To Kumu Hula in the Diaspora: consider suggesting to ʻōlapa to use onion skins in place of ʻōlena when needed to dye materials for garments and hula implements where appropriate.

Rosemary - Rosmarinus officinalis

This Mediterranean herb thrives in Bay Area gardens.

rosemary plant.

Plant Parts Used: Leaves and stems

Colors Achieved: leaves —> Yellow-green, olive, soft sage tones. leaves with stems —> may also produce a warm tan color. Results vary significantly between plant varieties and old vs. new growth.

Extraction Method: Use fresh or dried material, simmer for 1 hour. Fresh material gives brighter colors.

Bay Area Availability: Year-round; grows abundantly in Bay Area gardens

Harvesting Notes: Best harvested in late spring and early summer when oils are most concentrated.

To Kumu Hula in the Diaspora: consider suggesting to ʻōlapa to use old rosemary woody stems to produce warm natural aged kapa colors. First test various rosemary plant sources and plant parts to find ideal color for this.

Lavender - Lavandula

Another Mediterranean plant that flourishes in our climate.

lavender plants.

Plant Parts Used: Flowers and stems

Colors Achieved: Soft purples, grays, and mauves

Extraction Method: Use fresh or dried flowers, simmer gently for 30 minutes. Over-boiling can muddy the colors.

Bay Area Availability: Peak season June-August, but available year-round

Cultural Adaptation: While not traditional to Hawaiʻi, lavender as myriad medicinal properties and can be adapted to the Hawaiian worldview in the diaspora, especially for spiritual kaona.

Japanese Indigo - Persicaria tinctoria

This remarkable plant produces stunning blues and has potential to explore special fermentation techniques. An alternative to ʻukiʻuki or pōpolo berry in various combinations.

Japanese indigo plant. Gardens at Kekoa Creative.

Plant Parts Used: Fresh leaves only

Colors Achieved: Deep blues, from light sky blue to rich navy

Extraction Method: Fresh leaf indigo OR dye vat (requires fermentation - advanced)

Fresh Leaf - massage fresh leaves with salt and let stand for 20 minutes, add material for dyeing and massage leaf mash into undyed material until the desired color is achieved. DO NOT ADD ADDITIONAL WATER. Wring out and let oxidize in air. Repeat as many times as necessary to achieve color depth. Will need proportional weight of leaf to undyed material. Final oxidization and then rinse with fressh water to flush out green pigment, leaving only indigo blue.

Dye Vat - indigo leaf fermentation required. Indigo leaves are processed into indigo paste, then fermented with lime and sugar to create an alkaline vat for dyeing. Indigo pigments do not mix in water, and so fermentation is required to alter the dyeʻs molecular structure to be able to mixed into water and turn into a dye vat.

Bay Area Availability: Annual. Summer growing season (requires cultivation).

Note: Indigo dyeing is a complex process that deserves its own dedicated learning - consider taking a workshop to learn proper techniques.

Eucalyptus - Eucalyptus globulus

Abundant throughout the Bay Area, different parts yield different colors.

Eucalyptus tree forest.

Plant Parts Used:

Fresh leaves: Produce coral, pink, and orange tones

Bark: Yields deeper reds and rust colors

Seed pods: Create yellow and tan colors

Extraction Methods:

Leaves: Simmer fresh leaves for 1 hour

Bark: Simmer for 2-3 hours for deep colors

Seed pods: Simmer for 45 minutes

Bay Area Availability: Year-round; extremely abundant

Harvesting Ethics: Only harvest from trees that are being pruned or removed - never damage living trees. Prioritize gathering fallen bark that has already shed from the trunk. This is a known to be an extremely flammable material influential in the exacerbation of California forest fires.

Avocado - Persea americana

A sustainable way to use kitchen waste.

avocados.

Plant Parts Used: Pits and skins

Colors Achieved:

Pits: Soft pink, coral, peachy tones

Skins: Deeper rose and burgundy colors

Extraction Method: Clean pits/skins, simmer for 2-3 hours. Pits can be chopped or grated for faster color extraction.

Bay Area Availability: Year-round from kitchen scraps

Sustainability Note: Perfect example of zero-waste dyeing practices.

Basic Extraction Methods for Beginners

Hot Water Extraction (Most Common)

Prepare plant material: Chop, crush, or break apart to increase surface area

Ratio: Use 1:1 ratio of plant material to fabric weight (100g plant material for 100g fabric)

Simmer: Add plant material to water, simmer 30 minutes to 3 hours depending on material

Strain: Remove plant material, keep the colored liquid (this is your dye bath)

Dye: Add pre-wetted, mordanted fabric to warm dye bath

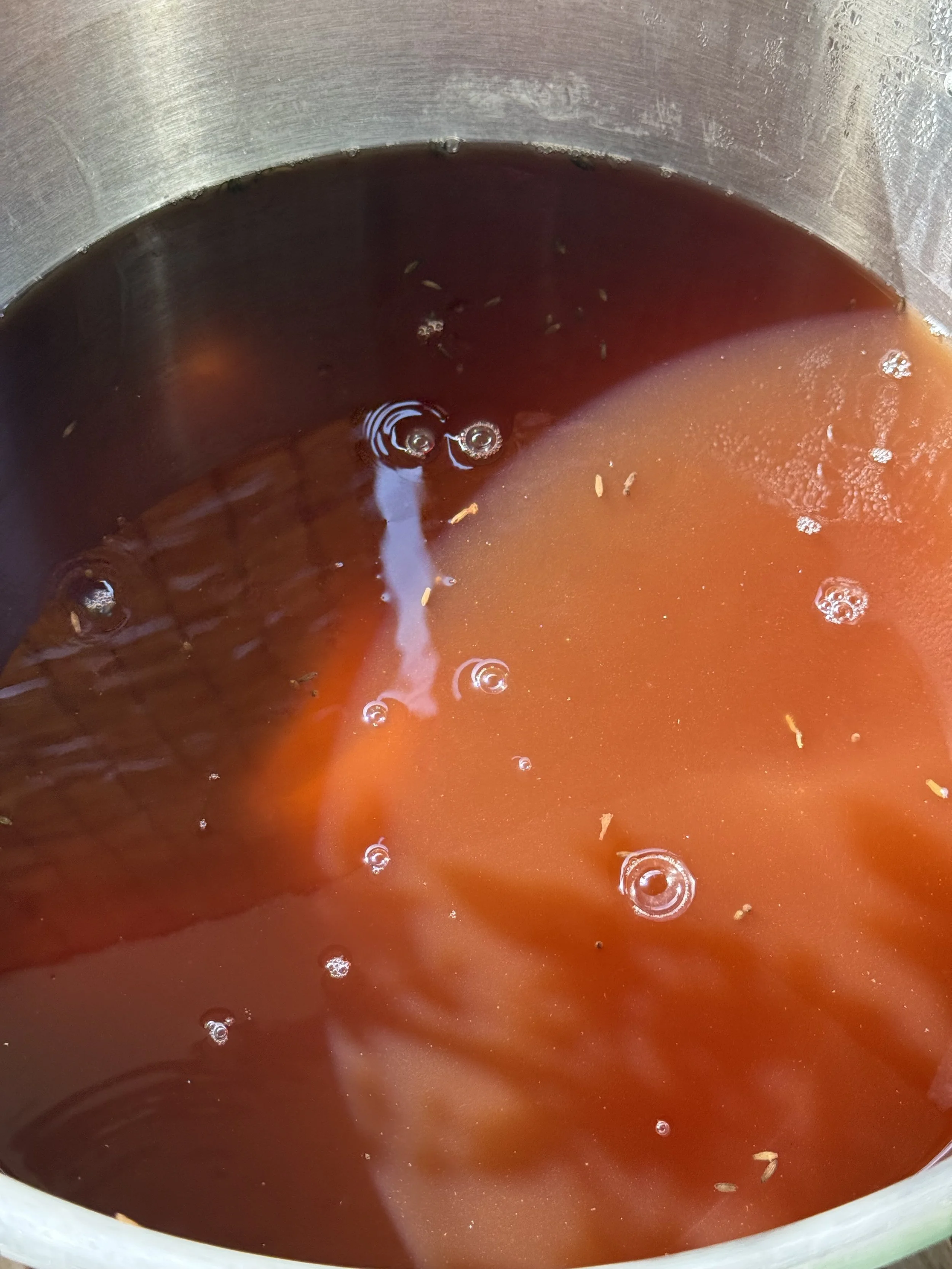

hot water extraction.

Cold Water Extraction

Some delicate flowers and leaves give better colors with cold extraction:

Soak: Place plant material in cold water for 24-48 hours

Strain: Remove plant material

Heat gently: Warm (don't boil) the dye bath before adding fabric

cold water extraction of onion skins.

Fermentation (Advanced)

For plants like indigo that require fermentation:

Harvest: Use only fresh plant material

Ferment: Follow specific fermentation recipes for each plant

Maintain: Keep fermentation vats at proper pH and temperature

Dye: Use special techniques for fermented dye baths

lavender fermentation vat.

Connecting with Local Indigenous Knowledge

As we adapt our Hawaiian practices to new lands, it's essential to connect responsibly with the Indigenous peoples of those lands. In the SF Bay Area, this means learning from Ohlone communities about native plants and traditional uses in the same way that settlers in Hawaiʻi should learn from kānaka ʻōiwi practices.

Approaching with Respect

Research first: Learn about local tribes and their current communities

Offer reciprocity: Bring something to share - knowledge, skills, or resources

Listen more than you speak: Indigenous knowledge holders have much to teach

Follow protocols: Each community has its own ways of sharing knowledge

Acceptance: Sometimes an answer to a question can just be “no.” That is okay, and it is the responsibility of the one asking to accept any answer, including “no.” Information and knowledge are not the same thing, and no one is entitled to anotherʻs knowledge. Knowledge is a privilege and holds inherent value and worth. When receiving a “no,” consider the potential reasons and internalize them. If there is opportunity to request again, and appropriate work has been done, then the original answer may change or it may not. Again, itʻs acceptance and there is wisdom in that.

Native Bay Area Dye Plants to Explore

(Always learn from Indigenous knowledge holders before harvesting)

California buckeye: Traditional source of soap and potential dye

Madrone bark: Used traditionally by local tribes

Oak galls: Create deep blacks and grays; natural tannin source, can be used as mordant

Elderberry: Produces blue-purple dyes from berries

Building Relationships

Attend cultural events: Many tribes host public educational events

Support Indigenous businesses: Purchase plants and materials from Native-owned sources

Share your knowledge: Hawaiian dyeing techniques can be valuable to share in return

Advocate: Support Indigenous land rights and cultural preservation

Seasonal Harvesting Guide for Bay Area Dyers

Spring (March-May)

Rosemary: Peak oil content for strongest colors

Fresh eucalyptus leaves: New growth provides vibrant colors

Onion skins: Accumulate from spring cooking

Japanese indigo: Start seeds indoors for summer growing

Connect with local tribes: Many hold spring gathering events

Summer (June-August)

Lavender: Peak bloom time for strongest purples

Japanese indigo: Harvest leaves for fresh indigo dyeing

Eucalyptus bark: Dry season makes bark easier to harvest

Native plant walks: Join Indigenous-led plant walks to learn about local species

Fall (September-November)

Eucalyptus leaves: Mature leaves provide deeper colors

Avocado season: Fresh pits and skins from seasonal fruit

Japanese indigo: Final harvest before frost

Acorn season: Learn about traditional acorn processing and oak gall harvesting

Winter (December-February)

Eucalyptus bark: Continued availability

Stored onion skins: Use accumulated skins from holiday cooking

Planning and preparation: Time to plan next year's dye garden

Indoor projects: Perfect time for processing stored materials and learning new techniques

Getting Started: Your Natural Dye Journey

Essential Supplies

Large stainless steel pot: For dye baths (never use aluminum)

Strainer: To remove plant material

Wooden spoons: For stirring (metal can affect colors)

Mordants: Alum (beginner-friendly, for bright colors), iron (for darker colors), copper (for greens)

pH strips: To test acidity/alkalinity

Natural fiber fabrics: Cotton, linen, wool, silk (synthetics don't take natural dyes well)

Basic Process

Mordant your fabric: Pre-treat with alum or other mordants to help colors stick

Prepare dye bath: Extract color from plant materials

Dye: Add wet fabric to warm dye bath, simmer gently

Rinse: Cool water rinse to remove excess dye

Dry: Hang away from direct sunlight

Safety Notes

Work in ventilated area: Very important. Many plants can cause respiratory irritation, but especially the mordants

Wear gloves: Protect hands from staining and plant irritants

Test for allergies: Try small amounts first if you have sensitive skin

Research toxicity: Some plants are toxic - always research before use

Building Your Practice

Start simple: Begin with onion skins and eucalyptus - they're forgiving and reliable

Keep records: Document your recipes, ratios, and results

Connect with others: Join local natural dye groups and online communities

Learn continuously: Take workshops, read books, and practice regularly

Modern Applications and Contemporary Practitioners

Today's Hawaiian businesses and cultural practitioners are finding innovative ways to incorporate natural dyeing into contemporary life while maintaining cultural authenticity.

Sustainable Fashion

Modern Hawaiian designers and businesses like Kekoa Creative are using natural dyes to create:

Eco-friendly clothing lines that reduce environmental impact using reclaimed waste cotton and natural fibers

Culturally significant patterns that tell Hawaiian stories

Educational fashion that sparks conversations about sustainability and cultural preservation

Cultural Education

Natural dyeing workshops and classes are becoming powerful tools for:

Teaching Hawaiian values to younger generations

Connecting diaspora communities to ancestral practices

Building bridges between Hawaiian and Indigenous communities worldwide

Preserving traditional knowledge while adapting to contemporary contexts

Community Building

The practice of natural dyeing creates opportunities for:

Intergenerational learning where kūpuna share knowledge with younger generations

Cross-cultural exchange between Indigenous communities

Sustainable living education that connects to broader environmental movements

Therapeutic applications that support mental health and cultural grounding

Conclusion: Weaving Past and Present

Natural dyeing offers us a beautiful way to maintain our connection to Hawaiian culture while adapting to life in the diaspora. By learning to work with the plants available to us here in the Bay Area, we're not abandoning our traditions—we're evolving them.

Each piece of fabric we dye with onion skins or rosemary carries the same intention as those dyed with ʻōlena by our kūpuna. Each color we coax from Japanese indigo connects us to the same creative spirit that guided our ancestors' hands. And each time we gather in community to share this knowledge, we're ensuring that these practices continue to thrive.

The colors may come from different plants, but the mana—the cultural power and significance—remains the same. In adapting our practices to our new environment, we're not losing our culture; we're helping it grow and flourish in new soil. Some things may stay protected in the past, but others have potential to thrive in the future. It is true that the nature of things i ka wā kahiko, in the times past, were inherently different and cannot be replicated, but when we talk about a living people and culture, as long as kānaka ʻōiwi survive, then so can our practices, shaped and adapted to an ever changing world.

As we continue to explore natural dyeing in the diaspora, we honor both our Hawaiian heritage and our current home, creating something beautiful and meaningful that bridges past and present, tradition and innovation, Hawaiʻi and the Bay Area. Most importantly, we build relationships with the Indigenous peoples of our new lands, learning from each other and strengthening our collective knowledge.

Mālama ʻāina, mālama wai—caring for the land, caring for the water—wherever we are.

About Kekoa Creative: We are a Native Hawaiian-owned business based in the San Francisco Bay Area, dedicated to sustainable fashion and cultural education. Our naturally dyed pieces are created using locally sourced natural and organic fiber textiles, reclaimed waste cotton, and water-based or algae inks. Contact us at info@kekoacreative.com to learn more about our cultural workshops and sustainable fashion offerings.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Can I practice Hawaiian natural dyeing if I'm not Hawaiian? A: Yes, with respect and proper acknowledgment. This article focuses on adaptation and learning from Hawaiian traditions while being mindful of cultural appropriation. Always credit the source of knowledge and approach these practices with reverence for their cultural origins.

Q: Where can I source natural dye materials in the SF Bay Area? A: Many materials can be foraged locally (eucalyptus, acorns) or found at farmers markets (onion skins, avocado pits). For traditional Hawaiian plants like ʻōlena (turmeric), check Asian grocery stores or specialty spice shops. Always forage responsibly and with landowner permission.

Q: What's the difference between traditional Hawaiian and Bay Area natural dyes? A: Traditional Hawaiian dyeing uses native plants like kukui, ʻōlena, and koa bark. Bay Area adaptation incorporates locally available materials like eucalyptus, madrone bark, and California native plants while maintaining the same sustainable principles and techniques.

Q: How long do natural dyes last compared to synthetic dyes? A: Natural dyes can be quite lightfast when properly mordanted and cared for. While they may fade more gradually than synthetics, this creates beautiful, unique aging patterns that many consider part of their charm. Proper mordanting and aftercare significantly improve longevity.

Q: What fabrics work best for natural dyeing? A: Natural fibers like cotton, linen, silk, and wool take natural dyes best. Pre-treat fabrics with appropriate mordants - alum for protein fibers (silk, wool) and aluminum acetate or tannin for cellulose fibers (cotton, linen).

Q: Is natural dyeing safe to do at home? A: Yes, when following proper safety protocols. Always work in well-ventilated areas, wear gloves, and research any plants before use. Some mordants require careful handling, but many natural dyes are much safer than synthetic alternatives.

Q: How do I maintain the cultural integrity of these practices? A: Learn the cultural context, acknowledge the source traditions, and approach the practice with respect rather than appropriation. Consider supporting Native Hawaiian artisans and organizations, and always credit Hawaiian knowledge systems when sharing your work.

Q: Can I sell items dyed with these techniques? A: Yes, but be transparent about your methods and cultural inspiration. Avoid claiming authenticity to traditions that aren't yours, and consider how you can give back to the communities whose knowledge you're drawing from.